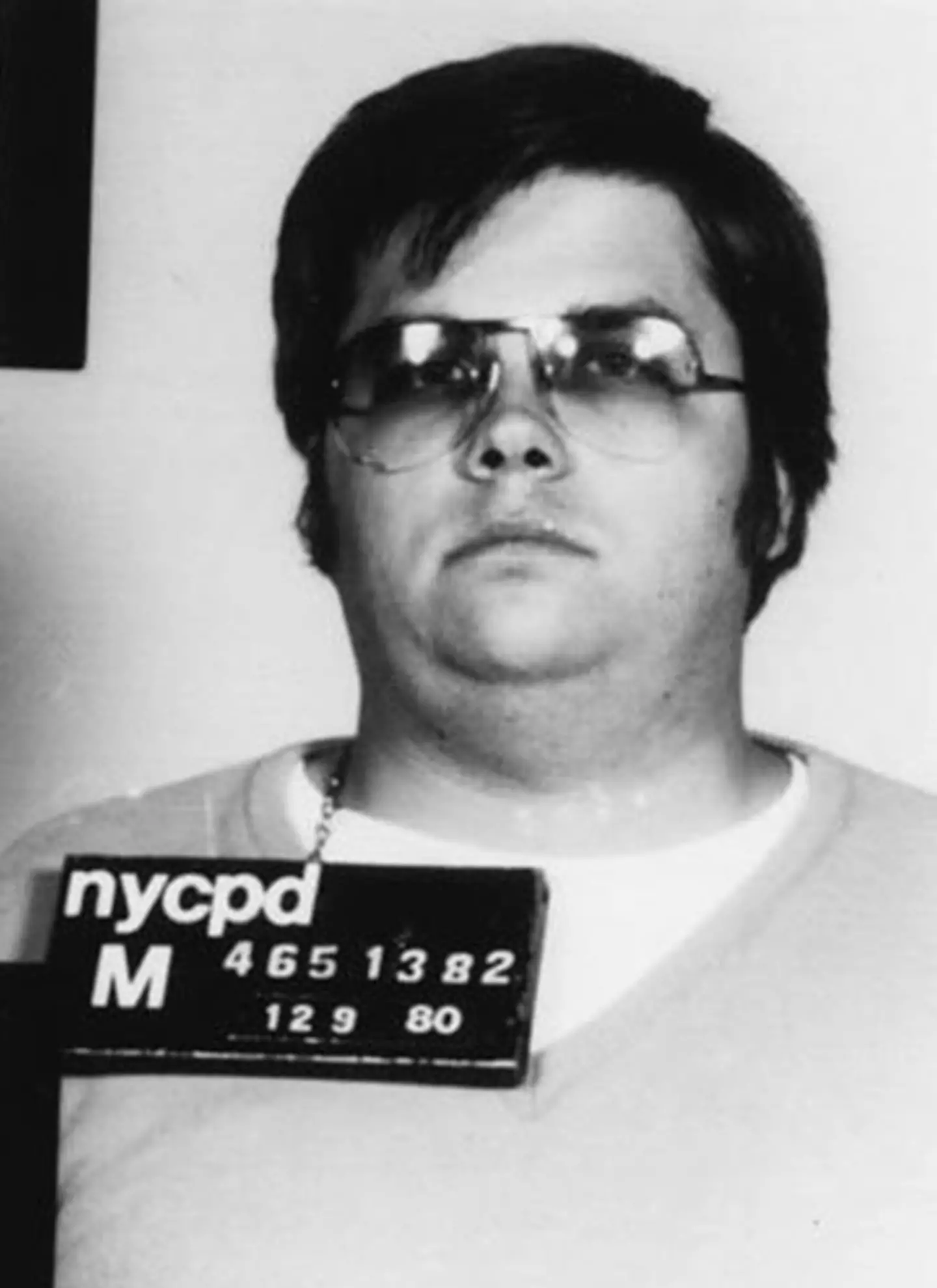

Four decades. Fourteen attempts. Still no freedom. Mark David Chapman, the man who silenced John Lennon, just faced the music again. And this time, he finally coughed up the real reason he pulled the trigger.

It was December 8, 1980. New York City. John Lennon, leaving his apartment, was shot four times from behind. A senseless act that stunned the world. For years, Chapman offered vague justifications, even calling Lennon a “phony.” But at his latest parole hearing, the truth, or at least a version of it, finally spilled out.

A Chillingly Selfish AmbitionForget the “phony” excuse. Chapman’s new tune? Pure, unadulterated selfishness. He admitted his crime was “for me and me alone.” He wanted to be “somebody.” To “be famous.” Lennon’s popularity wasn’t a grievance; it was a stepping stone. A grim ambition, indeed. And a chillingly calculated one.

“I don’t have to die and I can be a somebody,” he told the parole board, describing his twisted thought process. “I had sunk that low.” He even recalled the morning of the murder: “I just knew that was going to be the day that I was going to meet and kill him.”

He mumbled apologies. To Lennon’s family. To his friends. To the fans. He acknowledged the “devastation” and “agony” he caused. But then he added a crucial, chilling detail: “I had no thought about that at all at the time of the crime; I didn’t care.”

The Empathy GapThis is where Dr. Dannielle Haig, a psychologist, steps in. She listened closely to Chapman’s words. And she heard a gaping hole.

Chapman, she explains, demonstrates “cognitive empathy.” He can describe pain. He can understand sorrow. Intellectually. He can articulate the impact of his actions. He can even say the right words.

But “affective empathy”? That’s the deep, gut-wrenching feeling of another’s pain. That’s the emotional resonance. That’s what’s missing. Totally absent.

It’s like he’s reading from a script. A tell-tale sign, Haig warns, of “psychopathic traits.” Not always about overt violence, but an “emotional flatness.” A void where genuine remorse should be. Psychopathy, she notes, often manifests as a lack of “genuine remorse or moral emotion” like guilt or shame.

A Scripted Performance?The parole board, it seems, felt the same chill. They saw through the words. They ruled he lacked “genuine remorse or meaningful empathy.” They sensed the disconnect.

As Haig puts it, “When remorse feels scripted or overly reasoned, it suggests moral disengagement, not transformation.” He talks the talk, but he doesn’t feel the walk. True rehabilitation, she argues, involves “emotional integration.” The capacity to truly tolerate guilt, remorse, and grief. Without retreating into self-justification.

Chapman’s words may sound reflective. But, Haig concludes, “they lack that essential humanity.” He claims he wants to be “put under the rug somewhere,” that he doesn’t want to be famous anymore. But the board, and the psychologist, heard something else entirely.

So, the man who sought fame through murder will remain just that: a murderer. Behind bars. Until at least 2027. Some wounds never heal. Some lessons, it seems, are never truly learned.